Sunday, 12 December 2010

Saturday, 11 December 2010

Fairy tales and the printing press

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/arts/books/why-fairy-tales-are-immortal/article1805784/

About 50 years ago, critics were predicting the death of the fairy tale. They declared it would fizzle away in the domain of kiddie literature, while publishers sanitized its “harmful” effects. Academics, journalists and educators neglected it or considered it frivolous. Only the Austrian psychologist, Bruno Bettelheim tried to rescue the fairy tale in 1974 withThe Uses of Enchantment, but he treated it primarily as healthy therapy for children.

REVIEWED THIS WEEK

Bedtime Story, by Robert Wiersema

The best of the current crop

Luka and the Fire of Life, by Salman Rushdie

Virals, by Kathy Reichs

The Steps Across the Water, by Adam Gopnik

So, the fairy tale shrugged off his help and laughed at its critics. Indeed, most of those writers predicting its demise are long since dead. In the meantime, the fairy tale has flourished for not only for children, but for adults, everywhere you turn – in cinema, opera, theatre, books, storytelling festivals, graphic novels, computer games, television, the Internet, even iPads.

The fairy tale arose from a wide variety of tiny tales thousands of years ago. They were widespread throughout the world and continue in our own day, though the older forms and contents have changed to reflect new realities and preoccupations. As a simple, imaginative oral tale that contained magical and miraculous elements, it was originally related to the belief systems, values, rites and experiences of pagan peoples. Known also as the wonder or magic tale, the fairy tale underwent numerous transformations before the invention of the printing press in the 15th century led to the production of fixed texts and conventions of telling and reading.

But even then, the fairy tale refused to be dominated by print requirements; it continued to be altered and diffused by word of mouth. That is, it shaped and was shaped by the interaction of oral performances and print and other technological innovations: painting, photography, radio, film etc. In particular, technological inventions have enabled it to expand in various cultural domains, even the Internet, which can incorporate animation..

Like most popular art forms, the fairy tale adapted itself and was transformed by both common non-literate people and by upper-class literate people. From a simple brief tale with vital information about human preoccupations, it evolved into a volatile and fluid genre with a wide network. The fairy tale grew, became enormous and disseminated information that contributed to the cultural evolution of diverse groups.

In fact, it continues to grow and to embrace, if not swallow, all types of genres, art forms and cultural institutions, and adjusts itself to new environments through the human disposition for narrative and through technologies that make its diffusion easier and more effective. A vibrant fairy tale has the power to attract listeners and readers, to latch on to their brains and become a living force in cultural evolution.

Certain fairy tales resemble memes, a term coined by Richard Dawkins to represent the cultural evolution and dissemination of ideas and practices.. These tales form and inform us about human conflicts that continue to challenge us: Cinderella (abusive treatment of a stepchild), Little Red Riding Hood (rape), Bluebeard (serial killer), Hansel and Gretel (child abandonment),Donkey Skin (incest). In fact, the memetic classical tales and many others have enabled us – metaphorically – to focus on crucial human issues, to create – and recreate – possibilities for change.

At their best, fairy tales constitute the most profound articulation of the human struggle to form and maintain a civilizing process. They depict symbolically the opportunities for humans to adapt to changing environments, and they reflect the conflicts that arise when we fail to establish civilizing codes commensurate with the needs of large groups. The more we learn to relate to other groups and realize that their survival is linked to ours, the more we might construct social codes that guarantee humane relationships. In this regard, many fairy tales are utopian, but they are also uncanny because they tell us what we need, and unsettle us by showing what we lack and how we might compensate.

Fairy tales hint of happiness. We create works of art that contain traces, signs, forms and patterns that anticipate and illuminate ways into the future. We do not know happiness, but we instinctually know and feel that it can be created and perhaps even defined. Fairy tales map out possible ways of attaining happiness; they expose and resolve deep-rooted moral conflicts. The effectiveness of fairy tales and other forms of fantastic literature depends on the innovative manner in which we make them relevant for listeners and readers.

As our environment changes and evolves, so we change the media or modes of the tales to enable us to adapt to new conditions and shape instincts that were not necessarily generated for the world that we have created out of nature. This is perhaps one of the lessons that the best of fairy tales teach us: We are all misfit for the world, and yet, somehow we must all fit together.

Jack Zipes has published and lectured widely on fairy tales, their linguistic roots and their “socialization function.” He has written or edited more than 30 books, including Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, to be published next year.

About 50 years ago, critics were predicting the death of the fairy tale. They declared it would fizzle away in the domain of kiddie literature, while publishers sanitized its “harmful” effects. Academics, journalists and educators neglected it or considered it frivolous. Only the Austrian psychologist, Bruno Bettelheim tried to rescue the fairy tale in 1974 withThe Uses of Enchantment, but he treated it primarily as healthy therapy for children.

REVIEWED THIS WEEK

Bedtime Story, by Robert Wiersema

The best of the current crop

Luka and the Fire of Life, by Salman Rushdie

Virals, by Kathy Reichs

The Steps Across the Water, by Adam Gopnik

So, the fairy tale shrugged off his help and laughed at its critics. Indeed, most of those writers predicting its demise are long since dead. In the meantime, the fairy tale has flourished for not only for children, but for adults, everywhere you turn – in cinema, opera, theatre, books, storytelling festivals, graphic novels, computer games, television, the Internet, even iPads.

The fairy tale arose from a wide variety of tiny tales thousands of years ago. They were widespread throughout the world and continue in our own day, though the older forms and contents have changed to reflect new realities and preoccupations. As a simple, imaginative oral tale that contained magical and miraculous elements, it was originally related to the belief systems, values, rites and experiences of pagan peoples. Known also as the wonder or magic tale, the fairy tale underwent numerous transformations before the invention of the printing press in the 15th century led to the production of fixed texts and conventions of telling and reading.

But even then, the fairy tale refused to be dominated by print requirements; it continued to be altered and diffused by word of mouth. That is, it shaped and was shaped by the interaction of oral performances and print and other technological innovations: painting, photography, radio, film etc. In particular, technological inventions have enabled it to expand in various cultural domains, even the Internet, which can incorporate animation..

Like most popular art forms, the fairy tale adapted itself and was transformed by both common non-literate people and by upper-class literate people. From a simple brief tale with vital information about human preoccupations, it evolved into a volatile and fluid genre with a wide network. The fairy tale grew, became enormous and disseminated information that contributed to the cultural evolution of diverse groups.

In fact, it continues to grow and to embrace, if not swallow, all types of genres, art forms and cultural institutions, and adjusts itself to new environments through the human disposition for narrative and through technologies that make its diffusion easier and more effective. A vibrant fairy tale has the power to attract listeners and readers, to latch on to their brains and become a living force in cultural evolution.

Certain fairy tales resemble memes, a term coined by Richard Dawkins to represent the cultural evolution and dissemination of ideas and practices.. These tales form and inform us about human conflicts that continue to challenge us: Cinderella (abusive treatment of a stepchild), Little Red Riding Hood (rape), Bluebeard (serial killer), Hansel and Gretel (child abandonment),Donkey Skin (incest). In fact, the memetic classical tales and many others have enabled us – metaphorically – to focus on crucial human issues, to create – and recreate – possibilities for change.

At their best, fairy tales constitute the most profound articulation of the human struggle to form and maintain a civilizing process. They depict symbolically the opportunities for humans to adapt to changing environments, and they reflect the conflicts that arise when we fail to establish civilizing codes commensurate with the needs of large groups. The more we learn to relate to other groups and realize that their survival is linked to ours, the more we might construct social codes that guarantee humane relationships. In this regard, many fairy tales are utopian, but they are also uncanny because they tell us what we need, and unsettle us by showing what we lack and how we might compensate.

Fairy tales hint of happiness. We create works of art that contain traces, signs, forms and patterns that anticipate and illuminate ways into the future. We do not know happiness, but we instinctually know and feel that it can be created and perhaps even defined. Fairy tales map out possible ways of attaining happiness; they expose and resolve deep-rooted moral conflicts. The effectiveness of fairy tales and other forms of fantastic literature depends on the innovative manner in which we make them relevant for listeners and readers.

As our environment changes and evolves, so we change the media or modes of the tales to enable us to adapt to new conditions and shape instincts that were not necessarily generated for the world that we have created out of nature. This is perhaps one of the lessons that the best of fairy tales teach us: We are all misfit for the world, and yet, somehow we must all fit together.

Jack Zipes has published and lectured widely on fairy tales, their linguistic roots and their “socialization function.” He has written or edited more than 30 books, including Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, to be published next year.

Friday, 10 December 2010

http://www.123helpme.com/preview.asp?id=65209

Fairy Tales and Gender Roles

Some things about fairy tales we know to be true. They begin with "once upon a time." They end with "happily ever after." And somewhere in between the prince rescues the damsel in distress. Of course, this is not actually the case. Many fairytales omit these essential words. But few fairytales in the Western tradition indeed fail to have a beautiful, passive maiden rescued by a vibrant man, usually her superior in either social rank or in moral standing. Indeed, it is precisely the passivity of the women in fairy tales that has led so many progressive parents to wonder whether their children should be exposed to them. Can any girl ever really believe that she can grow up to be president or CEO or an astronaut after five viewings of Disney's "Snow White"?

Bacchilega (1997, chapter 2) chooses "Snow White" as a nearly pure form of gender archetype in the fairytale. She is mostly looking at Western traditions and focusing even more particularly on the two best known versions of this story in the West, the Disney animated movie and the Grimm Brothers' version of the tale. However, it is important to note (as Bacchilega herself does) that the Snow White tale has hundreds of oral versions collected from Asia Minor, Africa and the Americas as well as from across Europe. These tales of course vary in the details: The stepmother (or sometimes the mother herself) attacks Snow White in a variety of different ways, and the maiden is forced to take refu...

Fairy Tales and Gender Roles

Some things about fairy tales we know to be true. They begin with "once upon a time." They end with "happily ever after." And somewhere in between the prince rescues the damsel in distress. Of course, this is not actually the case. Many fairytales omit these essential words. But few fairytales in the Western tradition indeed fail to have a beautiful, passive maiden rescued by a vibrant man, usually her superior in either social rank or in moral standing. Indeed, it is precisely the passivity of the women in fairy tales that has led so many progressive parents to wonder whether their children should be exposed to them. Can any girl ever really believe that she can grow up to be president or CEO or an astronaut after five viewings of Disney's "Snow White"?

Bacchilega (1997, chapter 2) chooses "Snow White" as a nearly pure form of gender archetype in the fairytale. She is mostly looking at Western traditions and focusing even more particularly on the two best known versions of this story in the West, the Disney animated movie and the Grimm Brothers' version of the tale. However, it is important to note (as Bacchilega herself does) that the Snow White tale has hundreds of oral versions collected from Asia Minor, Africa and the Americas as well as from across Europe. These tales of course vary in the details: The stepmother (or sometimes the mother herself) attacks Snow White in a variety of different ways, and the maiden is forced to take refu...

http://www.surlalunefairytales.com/boardarchives/2003/jun2003/ftessay.html

The Origin and Development of the Fairy Tale

There is a certain quality in fairy tales that enthralls us as children, and inspires us as adults. Although fairy tales do not necessarily contain fairies, they all weave a tapestry of a magical world where fairies, and other supernatural beings, are possible. The term ìfairy taleî was coined in 17th century France. The French saying, conte de fÈe was translated into the English ìfairy taleî. To define what fairy tale itself is, is not easy, for often the line between fairy tale, myth, folk tale, and legend blurs. Many have tried, but the task of setting the parameters for genres is as messy and subjective as the science of taxonomy. However, it is generally accepted that most fairy tales have an undefined setting, ìonce upon a timeî and ìin a land far awayî, as well as characters with archetypical, static personalities. There also is an element of transformation in every fairy tale, whether it is from hideousness to beauty or from animal to man. Of course, the most important element of a fairy tale is itís other-worldliness ñ the ability to inspire wonder and give us a sense of the surreal. However, fairy tales existed before they were named, and as hard as it is to explain the essence of a fairy tale, it is an equal challenge to trace the origin of this vaguely defined genre. This is mainly because the literary fairy tale descended from an oral tradition, and tracing a story back to a particular source becomes a trial, as there is little written record. Also, some familiar, seemingly European tales may not be purely European, having been transposed from other cultures and edited to fit particular culture and class sensibilities. The development of the fairy tale genre was gradual and can be attributed to many sources, but there are certain people and places that have heavily contributed to the progression of fairy tales from their dark, common roots to the universal popularity they have achieved today.

The study of fairy tales is, nowadays, usually associated with study of childrenís literature, and given the ìfluffyî nature of present-day tales, it is understandable. However, for the first thousand years or more of their existence, fairy tales were part of an oral tradition that was told by adults, to adults. Stories descended through generations by being told and passed from one person to another, as part of a communal bonding process. This made a tale subject to change, dependent on the tellerís culture, values, and the desired moral lesson to be taken away by the listener. However, it was only when oral folklore was transcribed on paper that fairy tales solidified into a genre. The first instance of this be traced back to Ancient Egypt, during 1300 BC. In 200 AD, a European tale, Cupid and Psyche, of Greek/Roman origin, bearing similarity to Beauty and the Beast, was written by Apuleius. Across other cultures, literary tales emerged, such as the tale of Yeh-hsien, similar in storyline to Cinderella. Yeh-Shen was written in China between 850 and 860AD, and it chronicles the story of an orphaned girl that is mistreated by her fatherís co-wife and is helped by a fish who gifts her with finery and shoes of gold. Shen flees, leaving her shoe behind, and it is found by a merchant. Marveling at the smallness of her foot, the merchant takes Shen for his wife. By examining the elements of this Chinese tale, versus that of the European tale, one can see how a fairy tale is directly affected by the society the teller is from. We see the fish, symbolic of wisdom in Chinese culture, replaced with animals, or a fairy god mother. Shen is prized for the daintiness of her foot, while the standards of European beauty dwell little on feet. However, it was not until much later ñ the 15th century, that literary fairy tales began to flourish. Part of the cause was the invention of printing press, that fueled the rapid spread of ideas. Also a shift from of the emphasis of latin as the main language, to increased usage of the more common tongues, such as French, German and Dutch occurred. Because of this, the oral traditions of the common people were observed more frequently by those of the higher, more literate classes.

In England, the fairy tale genre was emerging, and elements of fairy tales can be seen in Shakespeareís Midsummer Nightís Eve and Chaucerís The Canterbury Tales. However, under the hand of the Puritan rule, such stories of fancy and amusement were discouraged, and so this stemmed the growth of folklore for many years. From 1690 ñ 1714 though, fairy tales enjoyed an unprecedented success in France, which had become a powerful and culturally dominant country. New ideas flourished. The most well-known figure in this period, in relation to fairy tales, was Charles Perrault, the author of favourites such as ìLittle Red Riding Hoodî, ìCinderellaî and ìBlue Beard.î His goal was to ìestablish the literary fairy tale as an innovate genre that exemplified a modern sensibility that was coming into its ownÖ equated with greatness of [the] French.î (p. 13) Perrault wanted to, through his fairy tales, glorify the ancient regime of France. However, the contributions made by women to the fairy tale genre, cannot be overlooked. Countess Catherine DíAulnoy was important in bringing the fairy tale in contact to French literary circles, thereby increasing itís acceptance has a genre. However, these fairy tales were usually written for adults, with sexuality, violence and complicated plots, with the purpose of either glorifying, criticizing, entertaining, or serving as satire. The idea of fairy tales as didactic literature surfaced in 1690, when FÈnelon, the Princeís tutor, wrote fairy tales for his pupil in the hopes of livening the dauphinís lessons. In 1756, Mme Le Prince Beaumont published ìMagasin de Enfantsî, a book of literary tales for the purpose of education, which she read to young girls. This played an important role in shaping the perception of fairy tales as childrenís literature, particular for the upper classes.

Three other male figures that played important roles in the development of fairy tales were the German brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, and a Dane by the name of Hans Christian Andersen. The Grimm brothers, renowned scholars of the German language, had oset out to preserve the oral tradition of their German culture. This was done by listening to and recording the oral tellings of tales, and it must be noted that most of the German folktales collected by the Grimms were told by women. Sisters, wives, sister-in-laws and friends recited tales that had been told by nursemaids, governesses, and servants. Eventually, a sizeable collection grew, with tales that were sometimes as dark as the surnames of their collectors- stories with overtones of sex, brutality and immorality. Although originally an effort to preserve the German culture, the Grimms soon realized that their tales appealed greatly to children. However, the content in many of the stories was deemed as objectionable. For example, the original version of Rapunzel had suggestions of pre-marital sex, seen when Rapunzel asked her mother ìwhy do you think my clothes have become too tight for me?î To make these tales acceptable to a young audience, the brothers set out to edit and add to their stories, making them less harsh, less cruel and more moral in nature. This censoring of stories represents another great leap of fairy tales away from the adult realm, and toward the confines of a childís storybook.

The Origin and Development of the Fairy Tale

There is a certain quality in fairy tales that enthralls us as children, and inspires us as adults. Although fairy tales do not necessarily contain fairies, they all weave a tapestry of a magical world where fairies, and other supernatural beings, are possible. The term ìfairy taleî was coined in 17th century France. The French saying, conte de fÈe was translated into the English ìfairy taleî. To define what fairy tale itself is, is not easy, for often the line between fairy tale, myth, folk tale, and legend blurs. Many have tried, but the task of setting the parameters for genres is as messy and subjective as the science of taxonomy. However, it is generally accepted that most fairy tales have an undefined setting, ìonce upon a timeî and ìin a land far awayî, as well as characters with archetypical, static personalities. There also is an element of transformation in every fairy tale, whether it is from hideousness to beauty or from animal to man. Of course, the most important element of a fairy tale is itís other-worldliness ñ the ability to inspire wonder and give us a sense of the surreal. However, fairy tales existed before they were named, and as hard as it is to explain the essence of a fairy tale, it is an equal challenge to trace the origin of this vaguely defined genre. This is mainly because the literary fairy tale descended from an oral tradition, and tracing a story back to a particular source becomes a trial, as there is little written record. Also, some familiar, seemingly European tales may not be purely European, having been transposed from other cultures and edited to fit particular culture and class sensibilities. The development of the fairy tale genre was gradual and can be attributed to many sources, but there are certain people and places that have heavily contributed to the progression of fairy tales from their dark, common roots to the universal popularity they have achieved today.

The study of fairy tales is, nowadays, usually associated with study of childrenís literature, and given the ìfluffyî nature of present-day tales, it is understandable. However, for the first thousand years or more of their existence, fairy tales were part of an oral tradition that was told by adults, to adults. Stories descended through generations by being told and passed from one person to another, as part of a communal bonding process. This made a tale subject to change, dependent on the tellerís culture, values, and the desired moral lesson to be taken away by the listener. However, it was only when oral folklore was transcribed on paper that fairy tales solidified into a genre. The first instance of this be traced back to Ancient Egypt, during 1300 BC. In 200 AD, a European tale, Cupid and Psyche, of Greek/Roman origin, bearing similarity to Beauty and the Beast, was written by Apuleius. Across other cultures, literary tales emerged, such as the tale of Yeh-hsien, similar in storyline to Cinderella. Yeh-Shen was written in China between 850 and 860AD, and it chronicles the story of an orphaned girl that is mistreated by her fatherís co-wife and is helped by a fish who gifts her with finery and shoes of gold. Shen flees, leaving her shoe behind, and it is found by a merchant. Marveling at the smallness of her foot, the merchant takes Shen for his wife. By examining the elements of this Chinese tale, versus that of the European tale, one can see how a fairy tale is directly affected by the society the teller is from. We see the fish, symbolic of wisdom in Chinese culture, replaced with animals, or a fairy god mother. Shen is prized for the daintiness of her foot, while the standards of European beauty dwell little on feet. However, it was not until much later ñ the 15th century, that literary fairy tales began to flourish. Part of the cause was the invention of printing press, that fueled the rapid spread of ideas. Also a shift from of the emphasis of latin as the main language, to increased usage of the more common tongues, such as French, German and Dutch occurred. Because of this, the oral traditions of the common people were observed more frequently by those of the higher, more literate classes.

In England, the fairy tale genre was emerging, and elements of fairy tales can be seen in Shakespeareís Midsummer Nightís Eve and Chaucerís The Canterbury Tales. However, under the hand of the Puritan rule, such stories of fancy and amusement were discouraged, and so this stemmed the growth of folklore for many years. From 1690 ñ 1714 though, fairy tales enjoyed an unprecedented success in France, which had become a powerful and culturally dominant country. New ideas flourished. The most well-known figure in this period, in relation to fairy tales, was Charles Perrault, the author of favourites such as ìLittle Red Riding Hoodî, ìCinderellaî and ìBlue Beard.î His goal was to ìestablish the literary fairy tale as an innovate genre that exemplified a modern sensibility that was coming into its ownÖ equated with greatness of [the] French.î (p. 13) Perrault wanted to, through his fairy tales, glorify the ancient regime of France. However, the contributions made by women to the fairy tale genre, cannot be overlooked. Countess Catherine DíAulnoy was important in bringing the fairy tale in contact to French literary circles, thereby increasing itís acceptance has a genre. However, these fairy tales were usually written for adults, with sexuality, violence and complicated plots, with the purpose of either glorifying, criticizing, entertaining, or serving as satire. The idea of fairy tales as didactic literature surfaced in 1690, when FÈnelon, the Princeís tutor, wrote fairy tales for his pupil in the hopes of livening the dauphinís lessons. In 1756, Mme Le Prince Beaumont published ìMagasin de Enfantsî, a book of literary tales for the purpose of education, which she read to young girls. This played an important role in shaping the perception of fairy tales as childrenís literature, particular for the upper classes.

Three other male figures that played important roles in the development of fairy tales were the German brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, and a Dane by the name of Hans Christian Andersen. The Grimm brothers, renowned scholars of the German language, had oset out to preserve the oral tradition of their German culture. This was done by listening to and recording the oral tellings of tales, and it must be noted that most of the German folktales collected by the Grimms were told by women. Sisters, wives, sister-in-laws and friends recited tales that had been told by nursemaids, governesses, and servants. Eventually, a sizeable collection grew, with tales that were sometimes as dark as the surnames of their collectors- stories with overtones of sex, brutality and immorality. Although originally an effort to preserve the German culture, the Grimms soon realized that their tales appealed greatly to children. However, the content in many of the stories was deemed as objectionable. For example, the original version of Rapunzel had suggestions of pre-marital sex, seen when Rapunzel asked her mother ìwhy do you think my clothes have become too tight for me?î To make these tales acceptable to a young audience, the brothers set out to edit and add to their stories, making them less harsh, less cruel and more moral in nature. This censoring of stories represents another great leap of fairy tales away from the adult realm, and toward the confines of a childís storybook.

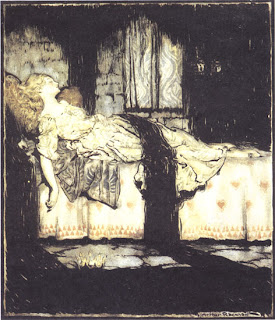

Little Snow White, The Brothers Grimm

Little Snow-White

by The Brothers Grimm

translated by Margaret Taylor (1884)

Once upon a time in the middle of winter, when the flakes of snow were falling like feathers from the sky, a queen sat at a window sewing, and the frame of the window was made of black ebony. And whilst she was sewing and looking out of the window at the snow, she pricked her finger with the needle, and three drops of blood fell upon the snow. And the red looked pretty upon the white snow, and she thought to herself, "Would that I had a child as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as the wood of the window-frame."

Soon after that she had a little daughter, who was as white as snow, and as red as blood, and her hair was as black as ebony; and she was therefore called Little Snow-white. And when the child was born, the Queen died.

After a year had passed the King took to himself another wife. She was a beautiful woman, but proud and haughty, and she could not bear that anyone else should surpass her in beauty. She had a wonderful looking-glass, and when she stood in front of it and looked at herself in it, and said --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?"

the looking-glass answered --

"Thou, O Queen, art the fairest of all!"

Then she was satisfied, for she knew that the looking-glass spoke the truth.

But Snow-white was growing up, and grew more and more beautiful; and when she was seven years old she was as beautiful as the day, and more beautiful than the Queen herself. And once when the Queen asked her looking-glass --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?" it answered --

"Thou art fairer than all who are here, Lady Queen."

But more beautiful still is Snow-white, as I ween."

Then the Queen was shocked, and turned yellow and green with envy. From that hour, whenever she looked at Snow-white, her heart heaved in her breast, she hated the girl so much.

And envy and pride grew higher and higher in her heart like a weed, so that she had no peace day or night. She called a huntsman, and said, "Take the child away into the forest; I will no longer have her in my sight. Kill her, and bring me back her heart as a token." The huntsman obeyed, and took her away; but when he had drawn his knife, and was about to pierce Snow-white's innocent heart, she began to weep, and said, "Ah dear huntsman, leave me my life! I will run away into the wild forest, and never come home again."

And as she was so beautiful the huntsman had pity on her and said, "Run away, then, you poor child." "The wild beasts will soon have devoured you," thought he, and yet it seemed as if a stone had been rolled from his heart since it was no longer needful for him to kill her. And as a young boar just then came running by he stabbed it, and cut out its heart and took it to the Queen as proof that the child was dead. The cook had to salt this, and the wicked Queen ate it, and thought she had eaten the heart of Snow-white.

But now the poor child was all alone in the great forest, and so terrified that she looked at every leaf of every tree, and did not know what to do. Then she began to run, and ran over sharp stones and through thorns, and the wild beasts ran past her, but did her no harm.

She ran as long as her feet would go until it was almost evening; then she saw a little cottage and went into it to rest herself. Everything in the cottage was small, but neater and cleaner than can be told. There was a table on which was a white cover, and seven little plates, and on each plate a little spoon; moreover, there were seven little knives and forks, and seven little mugs. Against the wall stood seven little beds side by side, and covered with snow-white counterpanes.

Little Snow-white was so hungry and thirsty that she ate some vegetables and bread from each plate and drank a drop of wine out of each mug, for she did not wish to take all from one only. Then, as she was so tired, she laid herself down on one of the little beds, but none of them suited her; one was too long, another too short, but at last she found that the seventh one was right, and so she remained in it, said a prayer and went to sleep.

When it was quite dark the owners of the cottage came back; they were seven dwarfs who dug and delved in the mountains for ore. They lit their seven candles, and as it was now light within the cottage they saw that someone had been there, for everything was not in the same order in which they had left it.

The first said, "Who has been sitting on my chair?"

The second, "Who has been eating off my plate?"

The third, "Who has been taking some of my bread?"

The fourth, "Who has been eating my vegetables?"

The fifth, "Who has been using my fork?"

The sixth, "Who has been cutting with my knife?"

The seventh, "Who has been drinking out of my mug?"

Then the first looked round and saw that there was a little hole on his bed, and he said, "Who has been getting into my bed?" The others came up and each called out, "Somebody has been lying in my bed too." But the seventh when he looked at his bed saw little Snow-white, who was lying asleep therein. And he called the others, who came running up, and they cried out with astonishment, and brought their seven little candles and let the light fall on little Snow-white. "Oh, heavens! oh, heavens!" cried they, "what a lovely child!" and they were so glad that they did not wake her up, but let her sleep on in the bed. And the seventh dwarf slept with his companions, one hour with each, and so got through the night.

When it was morning little Snow-white awoke, and was frightened when she saw the seven dwarfs. But they were friendly and asked her what her name was. "My name is Snow-white," she answered. "How have you come to our house?" said the dwarfs. Then she told them that her step-mother had wished to have her killed, but that the huntsman had spared her life, and that she had run for the whole day, until at last she had found their dwelling. The dwarfs said, "If you will take care of our house, cook, make the beds, wash, sew, and knit, and if you will keep everything neat and clean, you can stay with us and you shall want for nothing." "Yes," said Snow-white, "with all my heart," and she stayed with them. She kept the house in order for them; in the mornings they went to the mountains and looked for copper and gold, in the evenings they came back, and then their supper had to be ready. The girl was alone the whole day, so the good dwarfs warned her and said, "Beware of your step-mother, she will soon know that you are here; be sure to let no one come in."

But the Queen, believing that she had eaten Snow-white's heart, could not but think that she was again the first and most beautiful of all; and she went to her looking-glass and said --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?"

and the glass answered --

"Oh, Queen, thou art fairest of all I see,

But over the hills, where the seven dwarfs dwell,

Snow-white is still alive and well,

And none is so fair as she."

Then she was astounded, for she knew that the looking-glass never spoke falsely, and she knew that the huntsman had betrayed her, and that little Snow-white was still alive.

And so she thought and thought again how she might kill her, for so long as she was not the fairest in the whole land, envy let her have no rest. And when she had at last thought of something to do, she painted her face, and dressed herself like an old pedler-woman, and no one could have known her. In this disguise she went over the seven mountains to the seven dwarfs, and knocked at the door and cried, "Pretty things to sell, very cheap, very cheap." Little Snow-white looked out of the window and called out, "Good-day my good woman, what have you to sell?" "Good things, pretty things," she answered; "stay-laces of all colours," and she pulled out one which was woven of bright-coloured silk. "I may let the worthy old woman in," thought Snow-white, and she unbolted the door and bought the pretty laces. "Child," said the old woman, "what a fright you look; come, I will lace you properly for once." Snow-white had no suspicion, but stood before her, and let herself be laced with the new laces. But the old woman laced so quickly and so tightly that Snow-white lost her breath and fell down as if dead. "Now I am the most beautiful," said the Queen to herself, and ran away.

Not long afterwards, in the evening, the seven dwarfs came home, but how shocked they were when they saw their dear little Snow-white lying on the ground, and that she neither stirred nor moved, and seemed to be dead. They lifted her up, and, as they saw that she was laced too tightly, they cut the laces; then she began to breathe a little, and after a while came to life again. When the dwarfs heard what had happened they said, "The old pedler-woman was no one else than the wicked Queen; take care and let no one come in when we are not with you."

But the wicked woman when she had reached home went in front of the glass and asked --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?"

and it answered as before --

"Oh, Queen, thou art fairest of all I see,

But over the hills, where the seven dwarfs dwell,

Snow-white is still alive and well,

And none is so fair as she."

When she heard that, all her blood rushed to her heart with fear, for she saw plainly that little Snow-white was again alive. "But now," she said, "I will think of something that shall put an end to you," and by the help of witchcraft, which she understood, she made a poisonous comb. Then she disguised herself and took the shape of another old woman. So she went over the seven mountains to the seven dwarfs, knocked at the door, and cried, "Good things to sell, cheap, cheap!" Little Snow-white looked out and said, "Go away; I cannot let any one come in." "I suppose you can look," said the old woman, and pulled the poisonous comb out and held it up. It pleased the girl so well that she let herself be beguiled, and opened the door. When they had made a bargain the old woman said, "Now I will comb you properly for once." Poor little Snow-white had no suspicion, and let the old woman do as she pleased, but hardly had she put the comb in her hair than the poison in it took effect, and the girl fell down senseless. "You paragon of beauty," said the wicked woman, "you are done for now," and she went away.

But fortunately it was almost evening, when the seven dwarfs came home. When they saw Snow-white lying as if dead upon the ground they at once suspected the step-mother, and they looked and found the poisoned comb. Scarcely had they taken it out when Snow-white came to herself, and told them what had happened. Then they warned her once more to be upon her guard and to open the door to no one.

The Queen, at home, went in front of the glass and said --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?"

then it answered as before --

"Oh, Queen, thou art fairest of all I see,

But over the hills, where the seven dwarfs dwell,

Snow-white is still alive and well,

And none is so fair as she."

When she heard the glass speak thus she trembled and shook with rage. "Snow-white shall die," she cried, "even if it costs me my life!"

Thereupon she went into a quite secret, lonely room, where no one ever came, and there she made a very poisonous apple. Outside it looked pretty, white with a red cheek, so that everyone who saw it longed for it; but whoever ate a piece of it must surely die.

When the apple was ready she painted her face, and dressed herself up as a country-woman, and so she went over the seven mountains to the seven dwarfs. She knocked at the door. Snow-white put her head out of the window and said, "I cannot let any one in; the seven dwarfs have forbidden me." "It is all the same to me," answered the woman, "I shall soon get rid of my apples. There, I will give you one."

"No," said Snow-white, "I dare not take anything." "Are you afraid of poison?" said the old woman; "look, I will cut the apple in two pieces; you eat the red cheek, and I will eat the white." The apple was so cunningly made that only the red cheek was poisoned. Snow-white longed for the fine apple, and when she saw that the woman ate part of it she could resist no longer, and stretched out her hand and took the poisonous half. But hardly had she a bit of it in her mouth than she fell down dead. Then the Queen looked at her with a dreadful look, and laughed aloud and said, "White as snow, red as blood, black as ebony-wood! this time the dwarfs cannot wake you up again."

And when she asked of the Looking-glass at home --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?"

it answered at last --

"Oh, Queen, in this land thou art fairest of all."

Then her envious heart had rest, so far as an envious heart can have rest.

The dwarfs, when they came home in the evening, found Snow-white lying upon the ground; she breathed no longer and was dead. They lifted her up, looked to see whether they could find anything poisonous, unlaced her, combed her hair, washed her with water and wine, but it was all of no use; the poor child was dead, and remained dead. They laid her upon a bier, and all seven of them sat round it and wept for her, and wept three days long.

Then they were going to bury her, but she still looked as if she were living, and still had her pretty red cheeks. They said, "We could not bury her in the dark ground," and they had a transparent coffin of glass made, so that she could be seen from all sides, and they laid her in it, and wrote her name upon it in golden letters, and that she was a king's daughter. Then they put the coffin out upon the mountain, and one of them always stayed by it and watched it. And birds came too, and wept for Snow-white; first an owl, then a raven, and last a dove.

And now Snow-white lay a long, long time in the coffin, and she did not change, but looked as if she were asleep; for she was as white as snow, as red as blood, and her hair was as black as ebony.

It happened, however, that a king's son came into the forest, and went to the dwarfs' house to spend the night. He saw the coffin on the mountain, and the beautiful Snow-white within it, and read what was written upon it in golden letters. Then he said to the dwarfs, "Let me have the coffin, I will give you whatever you want for it." But the dwarfs answered, "We will not part with it for all the gold in the world." Then he said, "Let me have it as a gift, for I cannot live without seeing Snow-white. I will honour and prize her as my dearest possession." As he spoke in this way the good dwarfs took pity upon him, and gave him the coffin.

And now the King's son had it carried away by his servants on their shoulders. And it happened that they stumbled over a tree-stump, and with the shock the poisonous piece of apple which Snow-white had bitten off came out of her throat. And before long she opened her eyes, lifted up the lid of the coffin, sat up, and was once more alive. "Oh, heavens, where am I?" she cried. The King's son, full of joy, said, "You are with me," and told her what had happened, and said, "I love you more than everything in the world; come with me to my father's palace, you shall be my wife."

And Snow-white was willing, and went with him, and their wedding was held with great show and splendour. But Snow-white's wicked step-mother was also bidden to the feast. When she had arrayed herself in beautiful clothes she went before the Looking-glass, and said --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?"

the glass answered --

"Oh, Queen, of all here the fairest art thou,

But the young Queen is fairer by far as I trow."

Then the wicked woman uttered a curse, and was so wretched, so utterly wretched, that she knew not what to do. At first she would not go to the wedding at all, but she had no peace, and must go to see the young Queen. And when she went in she knew Snow-white; and she stood still with rage and fear, and could not stir. But iron slippers had already been put upon the fire, and they were brought in with tongs, and set before her. Then she was forced to put on the red-hot shoes, and dance until she dropped down dead.

http://classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/grimm/bl-grimm-snowwhite.htm

by The Brothers Grimm

translated by Margaret Taylor (1884)

Once upon a time in the middle of winter, when the flakes of snow were falling like feathers from the sky, a queen sat at a window sewing, and the frame of the window was made of black ebony. And whilst she was sewing and looking out of the window at the snow, she pricked her finger with the needle, and three drops of blood fell upon the snow. And the red looked pretty upon the white snow, and she thought to herself, "Would that I had a child as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as the wood of the window-frame."

Soon after that she had a little daughter, who was as white as snow, and as red as blood, and her hair was as black as ebony; and she was therefore called Little Snow-white. And when the child was born, the Queen died.

After a year had passed the King took to himself another wife. She was a beautiful woman, but proud and haughty, and she could not bear that anyone else should surpass her in beauty. She had a wonderful looking-glass, and when she stood in front of it and looked at herself in it, and said --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?"

the looking-glass answered --

"Thou, O Queen, art the fairest of all!"

Then she was satisfied, for she knew that the looking-glass spoke the truth.

But Snow-white was growing up, and grew more and more beautiful; and when she was seven years old she was as beautiful as the day, and more beautiful than the Queen herself. And once when the Queen asked her looking-glass --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?" it answered --

"Thou art fairer than all who are here, Lady Queen."

But more beautiful still is Snow-white, as I ween."

Then the Queen was shocked, and turned yellow and green with envy. From that hour, whenever she looked at Snow-white, her heart heaved in her breast, she hated the girl so much.

And envy and pride grew higher and higher in her heart like a weed, so that she had no peace day or night. She called a huntsman, and said, "Take the child away into the forest; I will no longer have her in my sight. Kill her, and bring me back her heart as a token." The huntsman obeyed, and took her away; but when he had drawn his knife, and was about to pierce Snow-white's innocent heart, she began to weep, and said, "Ah dear huntsman, leave me my life! I will run away into the wild forest, and never come home again."

And as she was so beautiful the huntsman had pity on her and said, "Run away, then, you poor child." "The wild beasts will soon have devoured you," thought he, and yet it seemed as if a stone had been rolled from his heart since it was no longer needful for him to kill her. And as a young boar just then came running by he stabbed it, and cut out its heart and took it to the Queen as proof that the child was dead. The cook had to salt this, and the wicked Queen ate it, and thought she had eaten the heart of Snow-white.

But now the poor child was all alone in the great forest, and so terrified that she looked at every leaf of every tree, and did not know what to do. Then she began to run, and ran over sharp stones and through thorns, and the wild beasts ran past her, but did her no harm.

She ran as long as her feet would go until it was almost evening; then she saw a little cottage and went into it to rest herself. Everything in the cottage was small, but neater and cleaner than can be told. There was a table on which was a white cover, and seven little plates, and on each plate a little spoon; moreover, there were seven little knives and forks, and seven little mugs. Against the wall stood seven little beds side by side, and covered with snow-white counterpanes.

Little Snow-white was so hungry and thirsty that she ate some vegetables and bread from each plate and drank a drop of wine out of each mug, for she did not wish to take all from one only. Then, as she was so tired, she laid herself down on one of the little beds, but none of them suited her; one was too long, another too short, but at last she found that the seventh one was right, and so she remained in it, said a prayer and went to sleep.

When it was quite dark the owners of the cottage came back; they were seven dwarfs who dug and delved in the mountains for ore. They lit their seven candles, and as it was now light within the cottage they saw that someone had been there, for everything was not in the same order in which they had left it.

The first said, "Who has been sitting on my chair?"

The second, "Who has been eating off my plate?"

The third, "Who has been taking some of my bread?"

The fourth, "Who has been eating my vegetables?"

The fifth, "Who has been using my fork?"

The sixth, "Who has been cutting with my knife?"

The seventh, "Who has been drinking out of my mug?"

Then the first looked round and saw that there was a little hole on his bed, and he said, "Who has been getting into my bed?" The others came up and each called out, "Somebody has been lying in my bed too." But the seventh when he looked at his bed saw little Snow-white, who was lying asleep therein. And he called the others, who came running up, and they cried out with astonishment, and brought their seven little candles and let the light fall on little Snow-white. "Oh, heavens! oh, heavens!" cried they, "what a lovely child!" and they were so glad that they did not wake her up, but let her sleep on in the bed. And the seventh dwarf slept with his companions, one hour with each, and so got through the night.

When it was morning little Snow-white awoke, and was frightened when she saw the seven dwarfs. But they were friendly and asked her what her name was. "My name is Snow-white," she answered. "How have you come to our house?" said the dwarfs. Then she told them that her step-mother had wished to have her killed, but that the huntsman had spared her life, and that she had run for the whole day, until at last she had found their dwelling. The dwarfs said, "If you will take care of our house, cook, make the beds, wash, sew, and knit, and if you will keep everything neat and clean, you can stay with us and you shall want for nothing." "Yes," said Snow-white, "with all my heart," and she stayed with them. She kept the house in order for them; in the mornings they went to the mountains and looked for copper and gold, in the evenings they came back, and then their supper had to be ready. The girl was alone the whole day, so the good dwarfs warned her and said, "Beware of your step-mother, she will soon know that you are here; be sure to let no one come in."

But the Queen, believing that she had eaten Snow-white's heart, could not but think that she was again the first and most beautiful of all; and she went to her looking-glass and said --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?"

and the glass answered --

"Oh, Queen, thou art fairest of all I see,

But over the hills, where the seven dwarfs dwell,

Snow-white is still alive and well,

And none is so fair as she."

Then she was astounded, for she knew that the looking-glass never spoke falsely, and she knew that the huntsman had betrayed her, and that little Snow-white was still alive.

And so she thought and thought again how she might kill her, for so long as she was not the fairest in the whole land, envy let her have no rest. And when she had at last thought of something to do, she painted her face, and dressed herself like an old pedler-woman, and no one could have known her. In this disguise she went over the seven mountains to the seven dwarfs, and knocked at the door and cried, "Pretty things to sell, very cheap, very cheap." Little Snow-white looked out of the window and called out, "Good-day my good woman, what have you to sell?" "Good things, pretty things," she answered; "stay-laces of all colours," and she pulled out one which was woven of bright-coloured silk. "I may let the worthy old woman in," thought Snow-white, and she unbolted the door and bought the pretty laces. "Child," said the old woman, "what a fright you look; come, I will lace you properly for once." Snow-white had no suspicion, but stood before her, and let herself be laced with the new laces. But the old woman laced so quickly and so tightly that Snow-white lost her breath and fell down as if dead. "Now I am the most beautiful," said the Queen to herself, and ran away.

Not long afterwards, in the evening, the seven dwarfs came home, but how shocked they were when they saw their dear little Snow-white lying on the ground, and that she neither stirred nor moved, and seemed to be dead. They lifted her up, and, as they saw that she was laced too tightly, they cut the laces; then she began to breathe a little, and after a while came to life again. When the dwarfs heard what had happened they said, "The old pedler-woman was no one else than the wicked Queen; take care and let no one come in when we are not with you."

But the wicked woman when she had reached home went in front of the glass and asked --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?"

and it answered as before --

"Oh, Queen, thou art fairest of all I see,

But over the hills, where the seven dwarfs dwell,

Snow-white is still alive and well,

And none is so fair as she."

When she heard that, all her blood rushed to her heart with fear, for she saw plainly that little Snow-white was again alive. "But now," she said, "I will think of something that shall put an end to you," and by the help of witchcraft, which she understood, she made a poisonous comb. Then she disguised herself and took the shape of another old woman. So she went over the seven mountains to the seven dwarfs, knocked at the door, and cried, "Good things to sell, cheap, cheap!" Little Snow-white looked out and said, "Go away; I cannot let any one come in." "I suppose you can look," said the old woman, and pulled the poisonous comb out and held it up. It pleased the girl so well that she let herself be beguiled, and opened the door. When they had made a bargain the old woman said, "Now I will comb you properly for once." Poor little Snow-white had no suspicion, and let the old woman do as she pleased, but hardly had she put the comb in her hair than the poison in it took effect, and the girl fell down senseless. "You paragon of beauty," said the wicked woman, "you are done for now," and she went away.

But fortunately it was almost evening, when the seven dwarfs came home. When they saw Snow-white lying as if dead upon the ground they at once suspected the step-mother, and they looked and found the poisoned comb. Scarcely had they taken it out when Snow-white came to herself, and told them what had happened. Then they warned her once more to be upon her guard and to open the door to no one.

The Queen, at home, went in front of the glass and said --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?"

then it answered as before --

"Oh, Queen, thou art fairest of all I see,

But over the hills, where the seven dwarfs dwell,

Snow-white is still alive and well,

And none is so fair as she."

When she heard the glass speak thus she trembled and shook with rage. "Snow-white shall die," she cried, "even if it costs me my life!"

Thereupon she went into a quite secret, lonely room, where no one ever came, and there she made a very poisonous apple. Outside it looked pretty, white with a red cheek, so that everyone who saw it longed for it; but whoever ate a piece of it must surely die.

When the apple was ready she painted her face, and dressed herself up as a country-woman, and so she went over the seven mountains to the seven dwarfs. She knocked at the door. Snow-white put her head out of the window and said, "I cannot let any one in; the seven dwarfs have forbidden me." "It is all the same to me," answered the woman, "I shall soon get rid of my apples. There, I will give you one."

"No," said Snow-white, "I dare not take anything." "Are you afraid of poison?" said the old woman; "look, I will cut the apple in two pieces; you eat the red cheek, and I will eat the white." The apple was so cunningly made that only the red cheek was poisoned. Snow-white longed for the fine apple, and when she saw that the woman ate part of it she could resist no longer, and stretched out her hand and took the poisonous half. But hardly had she a bit of it in her mouth than she fell down dead. Then the Queen looked at her with a dreadful look, and laughed aloud and said, "White as snow, red as blood, black as ebony-wood! this time the dwarfs cannot wake you up again."

And when she asked of the Looking-glass at home --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?"

it answered at last --

"Oh, Queen, in this land thou art fairest of all."

Then her envious heart had rest, so far as an envious heart can have rest.

The dwarfs, when they came home in the evening, found Snow-white lying upon the ground; she breathed no longer and was dead. They lifted her up, looked to see whether they could find anything poisonous, unlaced her, combed her hair, washed her with water and wine, but it was all of no use; the poor child was dead, and remained dead. They laid her upon a bier, and all seven of them sat round it and wept for her, and wept three days long.

Then they were going to bury her, but she still looked as if she were living, and still had her pretty red cheeks. They said, "We could not bury her in the dark ground," and they had a transparent coffin of glass made, so that she could be seen from all sides, and they laid her in it, and wrote her name upon it in golden letters, and that she was a king's daughter. Then they put the coffin out upon the mountain, and one of them always stayed by it and watched it. And birds came too, and wept for Snow-white; first an owl, then a raven, and last a dove.

And now Snow-white lay a long, long time in the coffin, and she did not change, but looked as if she were asleep; for she was as white as snow, as red as blood, and her hair was as black as ebony.

It happened, however, that a king's son came into the forest, and went to the dwarfs' house to spend the night. He saw the coffin on the mountain, and the beautiful Snow-white within it, and read what was written upon it in golden letters. Then he said to the dwarfs, "Let me have the coffin, I will give you whatever you want for it." But the dwarfs answered, "We will not part with it for all the gold in the world." Then he said, "Let me have it as a gift, for I cannot live without seeing Snow-white. I will honour and prize her as my dearest possession." As he spoke in this way the good dwarfs took pity upon him, and gave him the coffin.

And now the King's son had it carried away by his servants on their shoulders. And it happened that they stumbled over a tree-stump, and with the shock the poisonous piece of apple which Snow-white had bitten off came out of her throat. And before long she opened her eyes, lifted up the lid of the coffin, sat up, and was once more alive. "Oh, heavens, where am I?" she cried. The King's son, full of joy, said, "You are with me," and told her what had happened, and said, "I love you more than everything in the world; come with me to my father's palace, you shall be my wife."

And Snow-white was willing, and went with him, and their wedding was held with great show and splendour. But Snow-white's wicked step-mother was also bidden to the feast. When she had arrayed herself in beautiful clothes she went before the Looking-glass, and said --

"Looking-glass, Looking-glass, on the wall,

Who in this land is the fairest of all?"

the glass answered --

"Oh, Queen, of all here the fairest art thou,

But the young Queen is fairer by far as I trow."

Then the wicked woman uttered a curse, and was so wretched, so utterly wretched, that she knew not what to do. At first she would not go to the wedding at all, but she had no peace, and must go to see the young Queen. And when she went in she knew Snow-white; and she stood still with rage and fear, and could not stir. But iron slippers had already been put upon the fire, and they were brought in with tongs, and set before her. Then she was forced to put on the red-hot shoes, and dance until she dropped down dead.

http://classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/grimm/bl-grimm-snowwhite.htm

Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen: My Life as a Fairy Tale

(2001)

Download, Rent, or Stream in DVD Quality Now

| Starring: | Edward Atterton | Patrick Barlow | more » |

| Directed By: | Philip Saville |

| IMDB Rating: | 6.6/10 (172 votes) |

| Plot: | A fictionalized account of the young life of Hans Christian Andersen, a young man with a penchant for... |

| Genre(s): | Adventure | Drama | Family |

Hans Christian Andersen: My Life as a Fairy Tale Plot / Reviews:

A fictionalized account of the young life of Hans Christian Andersen, a young man with a penchant for storytelling but struggles to find his place in the world and gain the affection of the woman he adores. Interspersed throughout are brief interludes of the stories that will make Hans famous (The Nightingale, The Little Mermaid and The Snow Queen to name a few), which are intertwined with the events that surround his own life.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)