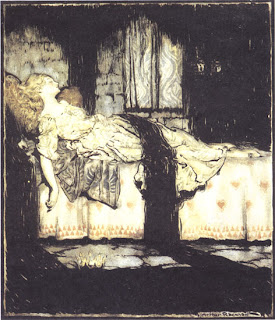

Graphic Fairy Tales, Whitney Sherratt

Sunday, 12 December 2010

Saturday, 11 December 2010

Fairy tales and the printing press

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/arts/books/why-fairy-tales-are-immortal/article1805784/

About 50 years ago, critics were predicting the death of the fairy tale. They declared it would fizzle away in the domain of kiddie literature, while publishers sanitized its “harmful” effects. Academics, journalists and educators neglected it or considered it frivolous. Only the Austrian psychologist, Bruno Bettelheim tried to rescue the fairy tale in 1974 withThe Uses of Enchantment, but he treated it primarily as healthy therapy for children.

REVIEWED THIS WEEK

Bedtime Story, by Robert Wiersema

The best of the current crop

Luka and the Fire of Life, by Salman Rushdie

Virals, by Kathy Reichs

The Steps Across the Water, by Adam Gopnik

So, the fairy tale shrugged off his help and laughed at its critics. Indeed, most of those writers predicting its demise are long since dead. In the meantime, the fairy tale has flourished for not only for children, but for adults, everywhere you turn – in cinema, opera, theatre, books, storytelling festivals, graphic novels, computer games, television, the Internet, even iPads.

The fairy tale arose from a wide variety of tiny tales thousands of years ago. They were widespread throughout the world and continue in our own day, though the older forms and contents have changed to reflect new realities and preoccupations. As a simple, imaginative oral tale that contained magical and miraculous elements, it was originally related to the belief systems, values, rites and experiences of pagan peoples. Known also as the wonder or magic tale, the fairy tale underwent numerous transformations before the invention of the printing press in the 15th century led to the production of fixed texts and conventions of telling and reading.

But even then, the fairy tale refused to be dominated by print requirements; it continued to be altered and diffused by word of mouth. That is, it shaped and was shaped by the interaction of oral performances and print and other technological innovations: painting, photography, radio, film etc. In particular, technological inventions have enabled it to expand in various cultural domains, even the Internet, which can incorporate animation..

Like most popular art forms, the fairy tale adapted itself and was transformed by both common non-literate people and by upper-class literate people. From a simple brief tale with vital information about human preoccupations, it evolved into a volatile and fluid genre with a wide network. The fairy tale grew, became enormous and disseminated information that contributed to the cultural evolution of diverse groups.

In fact, it continues to grow and to embrace, if not swallow, all types of genres, art forms and cultural institutions, and adjusts itself to new environments through the human disposition for narrative and through technologies that make its diffusion easier and more effective. A vibrant fairy tale has the power to attract listeners and readers, to latch on to their brains and become a living force in cultural evolution.

Certain fairy tales resemble memes, a term coined by Richard Dawkins to represent the cultural evolution and dissemination of ideas and practices.. These tales form and inform us about human conflicts that continue to challenge us: Cinderella (abusive treatment of a stepchild), Little Red Riding Hood (rape), Bluebeard (serial killer), Hansel and Gretel (child abandonment),Donkey Skin (incest). In fact, the memetic classical tales and many others have enabled us – metaphorically – to focus on crucial human issues, to create – and recreate – possibilities for change.

At their best, fairy tales constitute the most profound articulation of the human struggle to form and maintain a civilizing process. They depict symbolically the opportunities for humans to adapt to changing environments, and they reflect the conflicts that arise when we fail to establish civilizing codes commensurate with the needs of large groups. The more we learn to relate to other groups and realize that their survival is linked to ours, the more we might construct social codes that guarantee humane relationships. In this regard, many fairy tales are utopian, but they are also uncanny because they tell us what we need, and unsettle us by showing what we lack and how we might compensate.

Fairy tales hint of happiness. We create works of art that contain traces, signs, forms and patterns that anticipate and illuminate ways into the future. We do not know happiness, but we instinctually know and feel that it can be created and perhaps even defined. Fairy tales map out possible ways of attaining happiness; they expose and resolve deep-rooted moral conflicts. The effectiveness of fairy tales and other forms of fantastic literature depends on the innovative manner in which we make them relevant for listeners and readers.

As our environment changes and evolves, so we change the media or modes of the tales to enable us to adapt to new conditions and shape instincts that were not necessarily generated for the world that we have created out of nature. This is perhaps one of the lessons that the best of fairy tales teach us: We are all misfit for the world, and yet, somehow we must all fit together.

Jack Zipes has published and lectured widely on fairy tales, their linguistic roots and their “socialization function.” He has written or edited more than 30 books, including Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, to be published next year.

About 50 years ago, critics were predicting the death of the fairy tale. They declared it would fizzle away in the domain of kiddie literature, while publishers sanitized its “harmful” effects. Academics, journalists and educators neglected it or considered it frivolous. Only the Austrian psychologist, Bruno Bettelheim tried to rescue the fairy tale in 1974 withThe Uses of Enchantment, but he treated it primarily as healthy therapy for children.

REVIEWED THIS WEEK

Bedtime Story, by Robert Wiersema

The best of the current crop

Luka and the Fire of Life, by Salman Rushdie

Virals, by Kathy Reichs

The Steps Across the Water, by Adam Gopnik

So, the fairy tale shrugged off his help and laughed at its critics. Indeed, most of those writers predicting its demise are long since dead. In the meantime, the fairy tale has flourished for not only for children, but for adults, everywhere you turn – in cinema, opera, theatre, books, storytelling festivals, graphic novels, computer games, television, the Internet, even iPads.

The fairy tale arose from a wide variety of tiny tales thousands of years ago. They were widespread throughout the world and continue in our own day, though the older forms and contents have changed to reflect new realities and preoccupations. As a simple, imaginative oral tale that contained magical and miraculous elements, it was originally related to the belief systems, values, rites and experiences of pagan peoples. Known also as the wonder or magic tale, the fairy tale underwent numerous transformations before the invention of the printing press in the 15th century led to the production of fixed texts and conventions of telling and reading.

But even then, the fairy tale refused to be dominated by print requirements; it continued to be altered and diffused by word of mouth. That is, it shaped and was shaped by the interaction of oral performances and print and other technological innovations: painting, photography, radio, film etc. In particular, technological inventions have enabled it to expand in various cultural domains, even the Internet, which can incorporate animation..

Like most popular art forms, the fairy tale adapted itself and was transformed by both common non-literate people and by upper-class literate people. From a simple brief tale with vital information about human preoccupations, it evolved into a volatile and fluid genre with a wide network. The fairy tale grew, became enormous and disseminated information that contributed to the cultural evolution of diverse groups.

In fact, it continues to grow and to embrace, if not swallow, all types of genres, art forms and cultural institutions, and adjusts itself to new environments through the human disposition for narrative and through technologies that make its diffusion easier and more effective. A vibrant fairy tale has the power to attract listeners and readers, to latch on to their brains and become a living force in cultural evolution.

Certain fairy tales resemble memes, a term coined by Richard Dawkins to represent the cultural evolution and dissemination of ideas and practices.. These tales form and inform us about human conflicts that continue to challenge us: Cinderella (abusive treatment of a stepchild), Little Red Riding Hood (rape), Bluebeard (serial killer), Hansel and Gretel (child abandonment),Donkey Skin (incest). In fact, the memetic classical tales and many others have enabled us – metaphorically – to focus on crucial human issues, to create – and recreate – possibilities for change.

At their best, fairy tales constitute the most profound articulation of the human struggle to form and maintain a civilizing process. They depict symbolically the opportunities for humans to adapt to changing environments, and they reflect the conflicts that arise when we fail to establish civilizing codes commensurate with the needs of large groups. The more we learn to relate to other groups and realize that their survival is linked to ours, the more we might construct social codes that guarantee humane relationships. In this regard, many fairy tales are utopian, but they are also uncanny because they tell us what we need, and unsettle us by showing what we lack and how we might compensate.

Fairy tales hint of happiness. We create works of art that contain traces, signs, forms and patterns that anticipate and illuminate ways into the future. We do not know happiness, but we instinctually know and feel that it can be created and perhaps even defined. Fairy tales map out possible ways of attaining happiness; they expose and resolve deep-rooted moral conflicts. The effectiveness of fairy tales and other forms of fantastic literature depends on the innovative manner in which we make them relevant for listeners and readers.

As our environment changes and evolves, so we change the media or modes of the tales to enable us to adapt to new conditions and shape instincts that were not necessarily generated for the world that we have created out of nature. This is perhaps one of the lessons that the best of fairy tales teach us: We are all misfit for the world, and yet, somehow we must all fit together.

Jack Zipes has published and lectured widely on fairy tales, their linguistic roots and their “socialization function.” He has written or edited more than 30 books, including Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, to be published next year.

Friday, 10 December 2010

http://www.123helpme.com/preview.asp?id=65209

Fairy Tales and Gender Roles

Some things about fairy tales we know to be true. They begin with "once upon a time." They end with "happily ever after." And somewhere in between the prince rescues the damsel in distress. Of course, this is not actually the case. Many fairytales omit these essential words. But few fairytales in the Western tradition indeed fail to have a beautiful, passive maiden rescued by a vibrant man, usually her superior in either social rank or in moral standing. Indeed, it is precisely the passivity of the women in fairy tales that has led so many progressive parents to wonder whether their children should be exposed to them. Can any girl ever really believe that she can grow up to be president or CEO or an astronaut after five viewings of Disney's "Snow White"?

Bacchilega (1997, chapter 2) chooses "Snow White" as a nearly pure form of gender archetype in the fairytale. She is mostly looking at Western traditions and focusing even more particularly on the two best known versions of this story in the West, the Disney animated movie and the Grimm Brothers' version of the tale. However, it is important to note (as Bacchilega herself does) that the Snow White tale has hundreds of oral versions collected from Asia Minor, Africa and the Americas as well as from across Europe. These tales of course vary in the details: The stepmother (or sometimes the mother herself) attacks Snow White in a variety of different ways, and the maiden is forced to take refu...

Fairy Tales and Gender Roles

Some things about fairy tales we know to be true. They begin with "once upon a time." They end with "happily ever after." And somewhere in between the prince rescues the damsel in distress. Of course, this is not actually the case. Many fairytales omit these essential words. But few fairytales in the Western tradition indeed fail to have a beautiful, passive maiden rescued by a vibrant man, usually her superior in either social rank or in moral standing. Indeed, it is precisely the passivity of the women in fairy tales that has led so many progressive parents to wonder whether their children should be exposed to them. Can any girl ever really believe that she can grow up to be president or CEO or an astronaut after five viewings of Disney's "Snow White"?

Bacchilega (1997, chapter 2) chooses "Snow White" as a nearly pure form of gender archetype in the fairytale. She is mostly looking at Western traditions and focusing even more particularly on the two best known versions of this story in the West, the Disney animated movie and the Grimm Brothers' version of the tale. However, it is important to note (as Bacchilega herself does) that the Snow White tale has hundreds of oral versions collected from Asia Minor, Africa and the Americas as well as from across Europe. These tales of course vary in the details: The stepmother (or sometimes the mother herself) attacks Snow White in a variety of different ways, and the maiden is forced to take refu...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)